|

The Doolittle Tokyo Raid

The Doolittle Raid is the popular

name given to a mission undertaken during the Second World War by members of the United States Army Air Forces and the United

States Navy.

On April 18, 1942 -just over four

months since Japanese naval forces had bombed the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor, sixteen crews led by then- Lt. Col. "Jimmy" Doolittle

flew their B-25 Mitchell bombers off of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) in the first strike against the Japanese home

islands. The Doolittle Raiders attacked military and industrial targets in several Japanese cities and their surprise attack

on the previously untouched home island of Japan is considered by many historians to be a primary cause of the Japanese decisions

that let to the Battle of Midway during which the Japanese lost four aircraft carriers. It was the United States first major

strike back.

Many of the Doolittle Raiders continued

on in the service of their country. Many of them continued flying combat missions over enemy territory and several were killed

during the war on other missions. Three of the Raiders died within a day of the raid as a result of a crash landing and a

parachute failure (or too little altitude) and eight were imprisoned by the Japanese. Three of these men were executed by

the Japanese and another died for lack of proper treatment. Several of the Raiders ended up as prisoners of the Germans, and

participated in the real events that were portrayed in the film The Great Escape. Their leader, Jimmy Doolittle, continued

his brilliant career in the service of our country as the commander of the 12th Air Force and then the 8th Air Force which

contributed a great deal to the Allied victory in Europe.

After the war, many of the Raiders

continued in their country's service and several rose to high ranks in the Air Force. One of the men imprisoned by the Japanese

became a Christian during his prison stay and returned to Japan as a missionary. Still others returned to civilian life here

in the United States.

The Doolittle Tokyo raid was perhaps

the most famous exploit of the B-25 Mitchell. It was carried out in an attempt to shore up morale on the home front during

the early months of 1942, which was sagging as a result of suffering defeat after defeat in the Pacific.

Planning for a retaliatory raid on the Japanese

home islands seems to have begun very soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Contrary to general knowledge, Lt. Col. James

Doolittle was not the originator of the Tokyo raid concept. The basic idea of launching medium bombers from the deck of an

aircraft carrier seems to have come from Navy Captain Francis Low, who was on Admiral King's staff. Low took the idea to Captain

Duncan, Admiral King's air officer. Duncan concluded that the idea was technically feasible and passed it along to his boss.

The Admiral was enthusiastic about it, and on his orders, Capt. Duncan passed the idea along to General Arnold. General Arnold

then sent for his new special projects officer, Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle, who was already a famous aviator as a result

of his exploits with racing aircraft. Doolittle was enthusiastic about the idea and immediately signed on.

A "Tokyo project"

was quickly and secretly formed. Lt. Col. Doolittle and Captain Duncan were assigned project responsibilities for their respective

services. Lt. Col. Doolittle would lead a picked crew of aviators who would launch an attack against the Japanese home islands

from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet. Although it was believed that it was indeed feasible to launch medium bombers

from the deck of an aircraft carrier, it was impossible for these types of planes to land back on the deck of the carrier

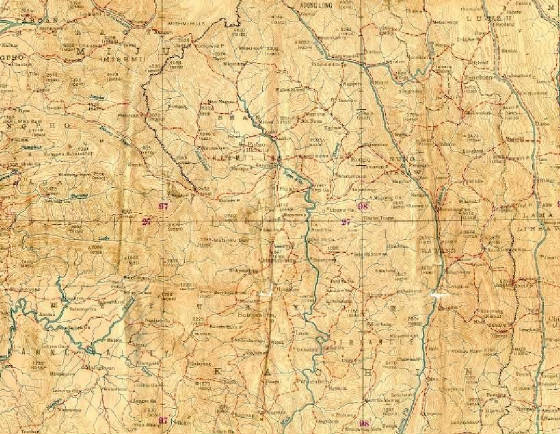

once the raid was over. Consequently, plans were made for the planes to be recovered at prearranged airfields in eastern China

at the end of the raid. From there, the bombers would continue on to Burma and enter service in General Stilwell's command.

The

plan required an aircraft with an overall range of 2400 miles carrying a 2000-pound bombload and capable of taking off from

the deck of an aircraft carrier. The only two possible candidates at the time were the Martin B-26 Marauder and the North

American B-25 Mitchell. The B-25 was selected on the basis of its superior takeoff performance.

At that time, the only

B-25s in service were with the 17th Bombardment Group. The 17th Bombardment Group comprised the 34th, 37th and 95th Squadrons,

plus the attached 89th Reconnaissance Squadron. This group had been transferred from Oregon to South Carolina in order to

meet the greater threat from German submarines operating off the East Coast. 24 B-25Bs were diverted from the 17th Bombardment

Group, and volunteers were recruited, the crews being told only that this was going to be a secret and very dangerous mission

against heavy odds.

Two Mitchells had been flown off the deck of the carrier, USS Hornet, on February 3, 1942, confirming

that the basic concept was feasible. The volunteers moved to Eglin Field in Florida for training. Still not knowing what kind

of mission they were training for, the crews practiced making takeoffs in as short a distance as possible. It was found that

with a reasonable headwind, a B-25 could get airborne with a 450-foot run.

Certain modifications had to be made to the

B-25Bs to make them suitable for the mission. Since the raid was going to be made at low level, the retractable ventral turret

was removed, saving about 600 pounds of weight. More fuel was added to the plane, bringing the total fuel load to 1241 gallons

-- 646 gallons in the wing tanks, 225 gallons in the bomb bay tank, 160 gallons in a collapsible tank carried in the crawlspace

above the bomb bay, 160 gallons in the ventral turret space, and ten 5-gallon cans for refills. The still-secret Norden bombsight

was removed, lest it fall into Japanese hands. It was replaced by a makeshift bombsight that proved more satisfactory for

low level operations. The bomb load consisted of four 500-pound bombs. As a deterrent against Japanese fighters making stern

attacks, a pair of dummy guns in the form of wooden sticks, painted black, were attached to the extreme rear fuselage, protruding

out the back of the transparent tail cap. Takeoff weight was about 31,000 pounds.

Upon completion of training, the crews left

Eglin Field for McClellan Field in California. On April 1, the crews departed McClellan for Alameda Naval Air Staion Base

near San Francisco. Sixteen B-25Bs were all that could be loaded onto the Hornet, although all of the crew members that trained

for the mission embarked aboard the carrier in case back-ups were needed. The task force steamed off toward Japan on April

2.

A chance encounter with a Japanese picket boat forced the raid to be launched at a distance greater than the 400 miles

offshore that had originally been planned and ten hours ahead of schedule in a rough sea. On April 18, 1942, Lt. Col. Doolittle's

plane took off from the Hornet, followed by the 15 others. They headed for Japan, which was over 700 miles away.

The Mitchells

successfully bombed targets in Kobe, Yokohama and Nagoya, as well as Tokyo. The bombing altitude was about 1500 feet. No aircraft

were lost over the target. However, bad weather prevented the flyers from finding their prearranged landing fields in China,

and eleven of the crews had to bail out while four others crash-landed. One B-25B (40-2242) was flown to Vladivostock, Russia

where both the aircraft and crew were interned.

All sixteen B-25s that took part in the mission were lost, seven men were

injured and three were killed. Eight crew members were taken prisoner by the Japanese. Only four of those eight survived the

war. The survivors who had landed in Japanese-controlled territory were sheltered and attended by courageous Chinese, and

for this the Japanese occupying force in China wrought full vengeance on the local population.

Doolittle at first told

his crews that he thought that the mission had been a total failure and that he expected a court martial upon his return to

the USA. Although all the aircraft were lost and the damage inflicted during the raid was minimal, the operation provided

an incalculable boost to American morale when just about everything else in the Pacific was going badly. It also pointed out

the vulnerability of the Japanese homeland to bomber attack, and four first-line fighter groups were retained in Japan rather

than being sent to the Solomon's where they were urgently needed. Instead of being court-martialed, Doolittle was promoted

to Brigadier General, awarded the Medal of Honor, and assigned a new command with greater responsibility.

This website is not intended to contain

the Raiders complete story.

To learn more about them, We suggest that you read some books listed on The Doolittle Raiders

or visit our official website for more details at www.doolittletokyoraiders.com

|